Experience Tumblr like never before

Orion - Blog Posts

The Adventures of Commander Moonikin Campos

Artemis I will be an enormous step toward humanity’s return to the Moon. This mission will be the first flight test of the integrated Space Launch System rocket and the Orion spacecraft — the same system that will send future Artemis astronauts to the Moon. That’s why NASA needs someone capable to test the vehicle. Someone with the necessary experience. Someone with the Right Stuff. (Or... stuffing).

Meet Commander Moonikin Campos. He is a manikin, or a replica human body. Campos is named after Arturo Campos, a trailblazing NASA employee who worked on Apollo missions. Arturo Campos’ skill as an electrical engineer was pivotal in the rescue efforts to help guide the Apollo 13 astronauts home.

As the leader of the mission, Commander Campos will be flying in the pilot’s seat for the length of the mission: a journey of 1.3 million miles (~2 million km) around the Moon and back to Earth. He's spent years training for this mission and he loves a challenge. Campos will be equipped with two radiation sensors and will have additional sensors under his headrest and behind his seat to record acceleration and vibration data throughout the mission.

Traveling with Campos are his quirky companions, Zohar and Helga. They’re part of a special experiment to measure radiation outside of the protective bubble of Earth’s atmosphere. Together with their commander, they’re excited to play a role in humanity’s next great leap. (And hopefully they can last the entire flight without getting on each other's nerves.)

Will our brave explorers succeed on their mission and ensure the success of future Artemis operations? Can Commander Moonikin Campos live up to the legacy of his heroic namesake?? And did anyone remember to bring snacks??? Get the answers in this thrilling three-part series!

In the first part of Commander Moonikin Campos’ journey, our trailblazing hero prepares for liftoff from NASA’s spaceport at Kennedy Space Center in Florida, gets acquainted with the new hardware aboard the Orion spacecraft, and meets his crewmates: Helga and Zohar!

In the second part of the trio’s adventure, Campos, Helga, and Zohar blast out of the Earth’s atmosphere with nearly 8.8 million pounds (4 million kg) of thrust powering their ascent. Next stop: the Moon!

In the final chapter of the Artemis I mission, Campos and friends prepare for their return home, including the last and most dangerous part of their journey: reentering Earth’s atmosphere at a screeching 25,000 miles per hour (40,000 kph).

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

NASA’s Artemis I Rocket is on the Launch Pad — and in Your Living Room

Artemis I will be the first integrated flight test of the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion spacecraft: the rocket and spacecraft that will send future astronauts to the Moon!

Before we embark on the uncrewed Artemis I mission to the Moon and back, the rocket and spacecraft will need to undergo a test at the launch pad called a “wet dress rehearsal.” This test will take the team at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida through every step of the launch countdown, including filling the rocket’s tanks with propellant.

But in the meantime, you can take a closer look at SLS and the Orion spacecraft by downloading the 3D model for free on the NASA app! You can view the SLS model in augmented reality by placing it virtually in your own environment – on your desk, for example. Or standing beside your family pet!

SLS and Orion join more than 40 other 3D models in the app, including BioSentinel, one of 10 CubeSats flying aboard Artemis I.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

Ready for a virtual adventure through the Orion Nebula?

Suspended in space, the stars that reside in the Orion Nebula are scattered throughout a dramatic dust-and-gas landscape of plateaus, mountains, and valleys that are reminiscent of the Grand Canyon. This visualization uses visible and infrared views, combining images from the Hubble Space Telescope and the Spitzer Space Telescope to create a three-dimensional visualization.

Learn more about Hubble’s celebration of Nebula November and see new nebula images, here.

You can also keep up with Hubble on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and Flickr!

Visualization credits: NASA, ESA, and F. Summers, G. Bacon, Z. Levay, J. DePasquale, L. Hustak, L. Frattare, M. Robberto, M. Gennaro (STScI), R. Hurt (Caltech/IPAC), M. Kornmesser (ESA); Acknowledgement: A. Fujii, R. Gendler

Discovering the Universe Through the Constellation Orion

Do you ever look up at the night sky and get lost in the stars? Maybe while you’re stargazing, you spot some of your favorite constellations. But did you know there’s more to constellations than meets the eye? They’re not just a bunch of imaginary shapes made up of stars — constellations tell us stories about the universe from our perspective on Earth.

What is a constellation?

A constellation is a named pattern of stars that looks like a particular shape. Think of it like connecting the dots. If you join the dots — stars, in this case — and use your imagination, the picture would look like an object, animal, or person. For example, the ancient Greeks believed an arrangement of stars in the sky looked like a giant hunter with a sword attached to his belt, so they named it after a famous hunter in their mythology, Orion. It’s one of the most recognizable constellations in the night sky and can be seen around the world. The easiest way to find Orion is to go outside on a clear night and look for three bright stars close together in an almost-straight line. These three stars represent Orion's belt. Two brighter stars to the north mark his shoulders, and two more to the south represent his feet.

Credit: NASA/STScI

Over time, cultures around the world have had different names and numbers of constellations depending on what people thought they saw. Today, there are 88 officially recognized constellations. Though these constellations are generally based on what we can see with our unaided eyes, scientists have also invented unofficial constellations for objects that can only be seen in gamma rays, the highest-energy form of light.

Perspective is everything

The stars in constellations may look close to each other from our point of view here on Earth, but in space they might be really far apart. For example, Alnitak, the star at the left side of Orion's belt, is about 800 light-years away. Alnilam, the star in the middle of the belt, is about 1,300 light-years away. And Mintaka, the star at the right side of the belt, is about 900 light-years away. Yet they all appear from Earth to have the same brightness. Space is three-dimensional, so if you were looking at the stars that make up the constellation Orion from another part of our galaxy, you might see an entirely different pattern!

The superstars of Orion

Now that we know a little bit more about constellations, let’s talk about the supercool cosmic objects that form them – stars! Though over a dozen stars make up Orion, two take center stage. The red supergiant Betelgeuse (Orion's right shoulder) and blue supergiant Rigel (Orion's left foot) stand out as the brightest members in the constellation.

Credit: Derrick Lim

Betelgeuse is a young star by stellar standards, about 10 million years old, compared to our nearly 5 billion-year-old Sun. The star is so huge that if it replaced the Sun at the center of our solar system, it would extend past the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter! But due to its giant mass, it leads a fast and furious life.

Betelgeuse is destined to end in a supernova blast. Scientists discovered a mysterious dimming of Betelgeuse in late 2019 caused by a traumatic outburst that some believed was a precursor to this cosmic event. Though we don’t know if this incident is directly related to an imminent supernova, there’s a tiny chance it might happen in your lifetime. But don't worry, Betelgeuse is about 550 light-years away, so this event wouldn't be dangerous to us – but it would be a spectacular sight.

Rigel is also a young star, estimated to be 8 million years old. Like Betelgeuse, Rigel is much larger and heavier than our Sun. Its surface is thousands of degrees hotter than Betelgeuse, though, making it shine blue-white rather than red. These colors are even noticeable from Earth. Although Rigel is farther from Earth than Betelgeuse (about 860 light-years away), it is intrinsically brighter than its companion, making it the brightest star in Orion and one of the brightest stars in the night sky.

Credit: Rogelio Bernal Andreo

Buckle up for Orion’s belt

Some dots that make up constellations are actually more than one star, but from a great distance they look like a single object. Remember Mintaka, the star at the far right side of Orion's belt? It is not just a single star, but actually five stars in a complex star system.

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/GSFC/M. Corcoran et al.; Optical: Eckhard Slawik

Sword or a stellar nursery?

Below the three bright stars of Orion’s belt lies his sword, where you can find the famous Orion Nebula. The nebula is only 1,300 light-years away, making it the closest large star-forming region to Earth. Because of its brightness and prominent location just below Orion’s belt, you can actually spot the Orion Nebula from Earth! But with a pair of binoculars, you can get a much more detailed view of the stellar nursery. It’s best visible in January and looks like a fuzzy “star” in the middle of Orion’s sword.

More to discover in constellations

In addition to newborn stars, Orion also has some other awesome cosmic objects hanging around. Scientists have discovered exoplanets, or planets outside of our solar system, orbiting stars there. One of those planets is a giant gas world three times more massive than Jupiter. It’s estimated that on average there is at least one planet for every star in our galaxy. Just think of all the worlds you may be seeing when you look up at the night sky!

It’s also possible that the Orion Nebula might be home to a black hole, making it the closest known black hole to Earth. Though we may never detect it, because no light can escape black holes, making them invisible. However, space telescopes with special instruments can help find black holes. They can observe the behavior of material and stars that are very close to black holes, helping scientists find clues that can lead them closer to discovering some of these most bizarre and fascinating objects in the cosmos.

Next time you go stargazing, remember that there’s more to the constellations than meets the eye. Let them guide you to some of the most incredible and mysterious objects of the cosmos — young stars, brilliant nebulae, new worlds, star systems, and even galaxies!

To keep up with the most recent stellar news, follow NASA Universe on Twitter and Facebook.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

Congratulations to the Winner of the Name the Artemis Moonikin Challenge!

Congratulations to Campos! After a very close competition among eight different names, the people have decided: Commander Moonikin Campos is launching on Artemis I, our first uncrewed flight test of the Space Launch System rocket and Orion spacecraft around the Moon later this year.

The name Campos is a dedication to Arturo Campos, electrical power subsystem manager for the Apollo 13 lunar module. He is remembered as not only a key player instrumental to the Apollo 13 crew’s safe return home, but as a champion for equality in the workplace. The final bracket challenge was between Campos and Delos, a reference to the island where Apollo and Artemis were born, according to Greek mythology.

The Moonikin is a male-bodied manikin previously used in Orion vibration tests. Campos will occupy the commander’s seat inside and wear a first-generation Orion Crew Survival System — a spacesuit Artemis astronauts will wear during launch, entry, and other dynamic phases of their missions. Campos' seat will be outfitted with sensors under the headrest and behind the seat to record acceleration and vibration data throughout the mission. Data from the Moonikin’s experience will inform us how to protect astronauts during Artemis II, the first mission around the Moon with crew in more than 50 years.

The Moonikin is one of three passengers flying in place of crew aboard Orion on the mission to test the systems that will take astronauts to the Moon for the next generation of exploration. Two female-bodied model human torsos, called phantoms, will also be aboard Orion. Zohar and Helga, the phantoms named by the Israel Space Agency and the German Aerospace Center respectively, will support an investigation called the Matroshka AstroRad Radiation Experiment to provide data on radiation levels during lunar missions.

Campos, Zohar, and Helga are really excited to begin the journey around the Moon and back. The Artemis I mission will be one of the first steps to establishing a long-term presence on and around the Moon under Artemis, and will help us prepare for humanity's next giant leap — sending the first astronauts to Mars.

Be sure to follow Campos, Zohar, and Helga on their journey by following @NASAArtemis on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space!

Name the Artemis Moonikin!

Choose your player!

As we gear up for our Artemis I mission to the Moon — the mission that will prepare us to send the first woman and the first person of color to the lunar surface — we have an important task for you (yes, you!). Artemis I will be the first integrated test flight of the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and the Orion crew capsule. Although there won’t be any humans aboard Orion, there will be a very important crewmember: the Moonikin!

The Moonikin is a manikin, or anatomical human model, that will be used to gather data on the vibrations that human crewmembers will experience during future Artemis missions. But the Moonikin is currently missing something incredibly important — a name!

There are eight names in the running, and each one reflects an important piece of NASA’s past or a reference to the Artemis program:

1. ACE

ACE stands for Artemis Crew Explorer. This is a very practical name, as the Moonikin will be a member of the first official “crew” aboard Artemis I.

The Moonikin will occupy the commander’s seat inside Orion, be equipped with two radiation sensors, and wear a first-generation Orion Crew Survival System suit—a spacesuit astronauts will wear during launch, entry, and other dynamic phases of their missions. The Moonikin will also be accompanied by phantoms, which are manikins without arms or legs: Zohar from the Israel Space Agency and Helga from the German Aerospace Center. Zohar and Helga will be participating in an investigation called the Matroshka AstroRad Radiation Experiment, which will provide valuable data on radiation levels experienced during missions to the Moon.

2. Campos

Campos is a reference to Arturo Campos, an electrical engineer at NASA who was instrumental to bringing the Apollo 13 crew safely back home.

Apollo 13 was on its way to attempt the third Moon landing when an oxygen tank exploded and forced the mission to abort. With hundreds of thousands of miles left in the journey, mission control teams at Johnson Space Center were forced to quickly develop procedures to bring the astronauts back home while simultaneously conserving power, water, and heat. Apollo 13 is considered a “successful failure,” because of the experience gained in rescuing the crew. In addition to being a key player in these efforts, Campos also established and served as the first president of the League of United Latin American Citizens Council 660, which was composed of Mexican-American engineers at NASA.

3. Delos

On June 26, 2017, our Terra satellite captured this image of the thousands of islands scattered across the Aegean Sea. One notable group, the Cyclades, sits in the central region of the Aegean. They encircle the tiny, sacred island of Delos.

According to Greek mythology, Delos was the island where the twin gods Apollo and Artemis were born.

The name is a recognition of the lessons learned during the Apollo program. Dr. Abe Silverstein, former director of NASA’s Glenn Research Center, said that he chose the name “Apollo” for the NASA's first Moon landing program because image of "Apollo riding his chariot across the Sun was appropriate to the grand scale of the proposed program." Between 1969 and 1972, we successfully landed 12 humans on the lunar surface — providing us with invaluable information as the Artemis program gears up to send the first woman and the first person of color to the Moon.

4. Duhart

Duhart is a reference to Dr. Irene Duhart Long, the first African American woman to serve in the Senior Executive Service at Kennedy Space Center. As chief medical officer at the Florida spaceport, she was the first woman and the first person of color to hold that position. Her NASA career spanned 31 years.

Working in a male-dominated field, Long confronted — and overcame — many obstacles and challenges during her decorated career. She helped create the Spaceflight and Life Sciences Training Program at Kennedy, in partnership with Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, a program that encouraged more women and people of color to explore careers in science.

5. Montgomery

Montgomery is a reference to Julius Montgomery, the first African American ever hired at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station to work as a technical professional. After earning a bachelor's degree at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, Montgomery served in the U.S. Air Force, where he earned a first class radio-telescope operator's license. Montgomery began his Cape Canaveral career in 1956 as a member of the “Range Rats,” technicians who repaired malfunctioning ballistic missiles.

Montgomery was also the first African American to desegregate and graduate from Brevard Engineering College, now the Florida Institute of Technology in Melbourne, Florida.

6. Rigel

Rigel is one of the 10 brightest stars in Earth's sky and forms part of the familiar constellation Orion. The blue supergiant is about 860 light-years from Earth.

The reference to Rigel is a nod toward the Orion spacecraft, which the Moonikin (and future Artemis astronauts!) will be riding aboard. Built to take humans farther than they’ve ever gone before, the Orion spacecraft will serve as the exploration vehicle that will carry crew into space and provide safe re-entry back to Earth.

7. Shackleton

Shackleton Crater is a crater on the Moon named after the Antarctic explorer, Ernest Shackleton. The interior of the crater receives almost no direct sunlight, which makes it very cold — the perfect place to find ice. Our Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft (LRO) returned data that ice may make up as much as 22% of the surface material in Shackleton!

Shackleton Crater is unique because even though most of it is permanently shadowed, three points on the rim remain collectively sunlit for more than 90% of the year. The crater is a prominent feature at the Moon’s South Pole, a region where NASA plans to send Artemis astronauts on future missions.

8. Wargo

Wargo is a reference to Michael Wargo, who represented NASA as the first Chief Exploration Scientist for the Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters. He was a leading contributor to the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS), which launched together on to the Moon and confirmed water existed there in 2009.

Throughout his time as an instructor at MIT and his 20-year career at NASA, Wargo was known as a science ambassador to the public, and for his ability to explain complex scientific challenges and discoveries to less technical audiences. Following his sudden death in 2013, the International Astronomical Union posthumously named a crater on the far side of the Moon in his honor.

Want to participate in the naming contest? Make sure you are following @NASAArtemis on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram to get notified about the bracket challenges between June 16 and June 28! Learn more about the Name the Artemis Moonikin Challenge here.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

One Step Closer to the Moon with the Artemis Program! 🌙

The past couple of weeks have been packed with milestones for our Artemis program — the program that will land the first woman and the next man on the Moon!

Artemis I will be an integrated, uncrewed test of the Orion spacecraft and Space Launch System (SLS) rocket before we send crewed flights to the Moon.

On March 2, 2021, we completed stacking the twin SLS solid rocket boosters for the Artemis I mission. Over several weeks, workers with NASA's Exploration Ground Systems used one of five massive cranes to place 10 booster segments and nose assemblies on the mobile launcher inside the Vehicle Assembly Building at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.

On March 18, 2021, we completed our Green Run hot fire test for the SLS core stage at Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. The core stage includes the flight computers, four RS-25 engines, and enormous propellant tanks that hold more than 700,000 gallons of super cold propellant. The test successfully ignited the core stage and produced 1.6 million pounds of thrust. The next time the core stage lights up will be when Artemis I launches on its mission to the Moon!

In coming days, engineers will examine the data and determine if the stage is ready to be refurbished, prepared for shipment, and delivered to KSC where it will be integrated with the twin solid rocket boosters and the other rocket elements.

We are a couple steps closer to landing boots on the Moon!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Spaceships Don’t Go to the Moon Until They’ve Gone Through Ohio

From the South, to the Midwest, to infinity and beyond. The Orion spacecraft for Artemis I has several stops to make before heading out into the expanse, and it can’t go to the Moon until it stops in Ohio. It landed at the Mansfield Lahm Regional Airport on Nov. 24, and then it was transferred to Plum Brook Station where it will undergo a series of environmental tests over the next four months to make sure it’s ready for space. Here are the highlights of its journey so far.

It’s a bird? It’s a whale? It’s the Super Guppy!

The 40-degree-and-extremely-windy weather couldn’t stop the massive crowd at Mansfield from waiting hours to see the Super Guppy land. Families huddled together as they waited, some decked out in NASA gear, including one astronaut costume complete with a helmet. Despite the delays, about 1,500 people held out to watch the bulbous airplane touch down.

Buckle up. It’s time for an extremely safe ride.

After Orion safely made it to Ohio, the next step was transporting it 41 miles to Plum Brook Station. It was loaded onto a massive truck to make the trip, and the drive lasted several hours as it slowly maneuvered the rural route to the facility. The 130-foot, 38-wheel truck hit a peak speed of about 20 miles per hour. It was the largest load ever driven through the state, and more than 700 utility lines were raised or moved in preparation to let the vehicle pass.

Calling us clean freaks would be an understatement.

Any person who even thinks about breathing near Orion has to be suited up. We’re talking “bunny” suit, shoe covers, beard covers, hoods, latex gloves – the works. One of our top priorities is keeping Orion clean during testing to prevent contaminants from sticking to the vehicle’s surface. These substances could cause issues for the capsule during testing and, more importantly, later during its flight around the Moon.

And liftoff of Orion… via crane.

On the ceiling of the Space Environments Complex at Plum Brook Station is a colossal crane used to move large pieces of space hardware into position for testing. It’s an important tool during pretest work, as it is used to lift Orion from the “verticator”—the name we use for the massive contraption used to rotate the vehicle from its laying down position into an upright testing orientation. After liftoff from the verticator, technicians then used the crane to install the spacecraft inside the Heat Flux System for testing.

It’s really not tin foil.

Although it looks like tin foil, the metallic material wrapped around Orion and the Heat Flux System—the bird cage-looking hardware encapsulating the spacecraft—is a material called Mylar. It’s used as a thermal barrier to help control which areas of the spacecraft get heated or cooled during testing. This helps our team avoid wasting energy heating and cooling spots unnecessarily.

Bake at 300° for 63 days.

It took a little over a week to prep Orion for its thermal test in the vacuum chamber. Now begins the 63-day process of heating and cooling (ranging from -250° to 300° Fahrenheit) the capsule to ensure it’s ready to withstand the journey around the Moon and back.

View more images of Orion’s transportation and preparation here.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

The Artemis Story: Where We Are Now and Where We’re Going

Using a sustainable architecture and sophisticated hardware unlike any other, the first woman and the next man will set foot on the surface of the Moon by 2024. Artemis I, the first mission of our powerful Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and Orion spacecraft, is an important step in reaching that goal.

As we close out 2019 and look forward to 2020, here’s where we stand in the Artemis story — and what to expect in 2020.

Cranking Up The Heat on Orion

The Artemis I Orion spacecraft arrived at our Plum Brook Station in Sandusky, Ohio, on Tuesday, Nov. 26 for in-space environmental testing in preparation for Artemis I.

This four-month test campaign will subject the spacecraft, consisting of its crew module and European-built service module, to the vacuum, extreme temperatures (ranging from -250° to 300° F) and electromagnetic environment it will experience during the three-week journey around the Moon and back. The goal of testing is to confirm the spacecraft’s components and systems work properly under in-space conditions, while gathering data to ensure the spacecraft is fit for all subsequent Artemis missions to the Moon and beyond. This is the final critical step before the spacecraft is ready to be joined with the Space Launch System rocket for this first test flight in 2020!

Bringing Everyone Together

On Dec. 9, we welcomed members of the public to our Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans for #Artemis Day and to get an up-close look at the hardware that will help power our Artemis missions. The 43-acre facility has more than enough room for guests and the Artemis I, II, and III rocket hardware! NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine formally unveiled the fully assembled core stage of our SLS rocket for the first Artemis mission to the Moon, then guests toured of the facility to see flight hardware for Artemis II and III. The full-day event — complete with two panel discussions and an exhibit hall — marked a milestone moment as we prepare for an exciting next phase in 2020.

Rolling On and Moving Out

Once engineers and technicians at Michoud complete functional testing on the Artemis I core stage, it will be rolled out of the Michoud factory and loaded onto our Pegasus barge for a very special delivery indeed. About this time last year, our Pegasus barge crew was delivering a test version of the liquid hydrogen tank from Michoud to NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville for structural testing. This season, the Pegasus team will be transporting a much larger piece of hardware — the entire core stage — on a slightly shorter journey to the agency’s nearby Stennis Space Center near Bay St. Louis, Mississippi.

Special Delivery

Why Stennis, you ask? The giant core stage will be locked and loaded into the B2 Test Stand there for the landmark Green Run test series. During the test series, the entire stage, including its extensive avionics and flight software systems, will be tested in full. The series will culminate with a hot fire of all four RS-25 engines and will certify the complex stage “go for launch.” The next time the core stage and its four engines fire as one will be on the launchpad at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Already Working on Artemis II

As Orion and SLS make progress toward the pad for Artemis I, employees at NASA centers and large and small companies across America are hard at work assembling and manufacturing flight hardware for Artemis II and beyond. The second mission of SLS and Orion will be a test flight with astronauts aboard that will go around the Moon before returning home. Our work today will pave the way for a new generation of moonwalkers and Artemis explorers.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

To the Moon and Beyond: Why Our SLS Rocket Is Designed for Deep Space

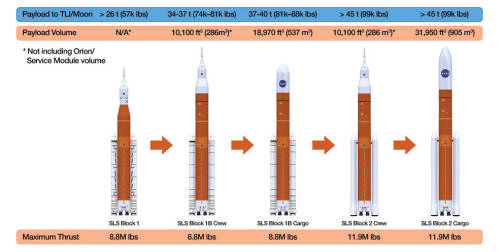

It will take incredible power to send the first woman and the next man to the Moon’s South Pole by 2024. That’s where America’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket comes in to play.

Providing more payload mass, volume capability and energy to speed missions through deep space than any other rocket, our SLS rocket, along with our lunar Gateway and Orion spacecraft, creates the backbone for our deep space exploration and Artemis lunar mission goals.

Here’s why our SLS rocket is a deep space rocket like no other:

It’s a heavy lifter

The Artemis missions will send humans 280,000 miles away from Earth. That’s 1,000 times farther into space than the International Space Station. To accomplish that mega feat, you need a rocket that’s designed to lift — and lift heavy. With help from a dynamic core stage — the largest stage we have ever built — the 5.75-million-pound SLS rocket can propel itself off the Earth. This includes the 57,000 pounds of cargo that will go to the Moon. To accomplish this, SLS will produce 15% more thrust at launch and during ascent than the Saturn V did for the Apollo Program.

We have the power

Where do our rocket’s lift and thrust capabilities come from? If you take a peek under our powerful rocket’s hood, so to speak, you’ll find a core stage with four RS-25 engines that produce more than 2 million pounds of thrust alongside two solid rocket boosters that each provide another 3.6 million pounds of thrust power. It’s a bold design. Together, they provide an incredible 8.8 million pounds of thrust to power the Artemis missions off the Earth. The engines and boosters are modified heritage hardware from the Space Shuttle Program, ensuring high performance and reliability to drive our deep space missions.

A rocket with style

While our rocket’s core stage design will remain basically the same for each of the Artemis missions, the SLS rocket’s upper stage evolves to open new possibilities for payloads and even robotic scientific missions to worlds farther away than the Moon like Mars, Saturn and Jupiter. For the first three Artemis missions, our SLS rocket uses an interim cryogenic propulsion stage with one RL10 engine to send Orion to the lunar south pole. For Artemis missions following the initial 2024 Moon landing, our SLS rocket will have an exploration upper stage with bigger fuel tanks and four RL10 engines so that Orion, up to four astronauts and larger cargoes can be sent to the Moon, too. Additional core stages and upper stages will support either crewed Artemis missions, science missions or cargo missions for a sustained presence in deep space.

It’s just the beginning

Crews at our Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans are in the final phases of assembling the core stage for Artemis I— and are already working on assembly for Artemis II.

Through the Artemis program, we aim not just to return humans to the Moon, but to create a sustainable presence there as well. While there, astronauts will learn to use the Moon’s natural resources and harness our newfound knowledge to prepare for the horizon goal: humans on Mars.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Top 5 Technologies Needed for a Spacecraft to Survive Deep Space

When a spacecraft built for humans ventures into deep space, it requires an array of features to keep it and a crew inside safe. Both distance and duration demand that spacecraft must have systems that can reliably operate far from home, be capable of keeping astronauts alive in case of emergencies and still be light enough that a rocket can launch it.

Missions near the Moon will start when the Orion spacecraft leaves Earth atop the world’s most powerful rocket, the Space Launch System. After launch from Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Orion will travel beyond the Moon to a distance more than 1,000 times farther than where the International Space Station flies in low-Earth orbit, and farther than any spacecraft built for humans has ever ventured. To accomplish this feat, Orion has built-in technologies that enable the crew and spacecraft to explore far into the solar system. Let’s check out the top five:

Systems to Live and Breathe

As humans travel farther from Earth for longer missions, the systems that keep them alive must be highly reliable while taking up minimal mass and volume. Orion will be equipped with advanced environmental control and life support systems designed for the demands of a deep space mission. A high-tech system already being tested aboard the space station will remove carbon dioxide (CO2) and humidity from inside Orion. The efficient system replaces many chemical canisters that would consume up to 10 percent of crew livable area. To save additional space, Orion will also have a new compact toilet, smaller than the one on the space station.

Highly reliable systems are critically important when distant crew will not have the benefit of frequent resupply shipments to bring spare parts from Earth. Even small systems have to function reliably to support life in space, from a working toilet to an automated fire suppression system or exercise equipment that helps astronauts stay in shape to counteract the zero-gravity environment. Distance from home also demands that Orion have spacesuits capable of keeping astronaut alive for six days in the event of cabin depressurization to support a long trip home.

Proper Propulsion

The farther into space a vehicle ventures, the more capable its propulsion systems need to be in order to maintain its course on the journey with precision and ensure its crew can get home.

Orion’s highly capable service module serves as the powerhouse for the spacecraft and provides propulsion capabilities that enable it to go around the Moon and back on exploration missions. The service module has 33 engines of various sizes. The main engine will provide major in-space maneuvering capabilities throughout the mission such as inserting Orion into lunar orbit and firing powerfully enough to exit orbit for a return trip to Earth. The other 32 engines are used to steer and control Orion on orbit.

In part due to its propulsion capabilities, including tanks that can hold nearly 2,000 gallons of propellant and a back up for the main engine in the event of a failure, Orion’s service module is equipped to handle the rigors of travel for missions that are both far and long. It has the ability to bring the crew home in a variety of emergency situations.

The Ability to Hold Off the Heat

Going to the Moon is no easy task, and it’s only half the journey. The farther a spacecraft travels in space, the more heat it will generate as it returns to Earth. Getting back safely requires technologies that can help a spacecraft endure speeds 30 times the speed of sound and heat twice as hot as molten lava or half as hot as the sun.

When Orion returns from the Moon it will be traveling nearly 25,000 mph, a speed that could cover the distance from Los Angeles to New York City in six minutes. Its advanced heat shield, made with a material called AVCOAT, is designed to wear away as it heats up. Orion’s heat shield is the largest of its kind ever built and will help the spacecraft withstand temperatures around 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit during reentry though Earth’s atmosphere.

Before reentry, Orion also will endure a 700-degree temperature range from about minus 150 to 550 degrees Fahrenheit. Orion’s highly capable thermal protection system, paired with thermal controls, will protect it during periods of direct sunlight and pitch black darkness while its crews comfortably enjoy a safe and stable interior temperature of about 77 degrees Fahrenheit.

Radiation Protection

As a spacecraft travels on missions beyond the protection of Earth’s magnetic field, it will be exposed to a harsher radiation environment than in low-Earth orbit with greater amounts of radiation from charged particles and solar storms. This kind of radiation can cause disruptions to critical computers, avionics and other equipment. Humans exposed to large amounts of radiation can experience both acute and chronic health problems ranging from near-term radiation sickness to the potential of developing cancer in the long-term.

Orion was designed from the start with built in system-level features to ensure reliability of essential elements of the spacecraft during potential radiation events. For example, Orion is equipped with four identical computers that each are self-checking, plus an entirely different backup computer, to ensure it can still send commands in the event of a disruption. Engineers have tested parts and systems to a high standard to ensure that all critical systems remain operable even under extreme circumstances.

Orion also has a makeshift storm shelter below the main deck of the crew module. In the event of a solar radiation event, we developed plans for crew on board to create a temporary shelter inside using materials on board. A variety of radiation sensors will also be on the spacecraft to help scientists better understand the radiation environment far away from Earth. One investigation, called AstroRad, will fly on Exploration Mission-1 and test an experimental vest that has the potential to help shield vital organs and decrease exposure from solar particle events.

Constant Communication and Navigation

Spacecraft venturing far from home go beyond the Global Positioning System (GPS) in space and above communication satellites in Earth orbit. To talk with mission control in Houston, Orion’s communication and navigation systems will switch from our Tracking and Data Relay Satellites (TDRS) system used by the International Space Station, and communicate through the Deep Space Network.

Orion is equipped with backup communication and navigation systems to help the spacecraft stay in contact with the ground and orient itself if its primary systems fail. The backup navigation system, a relatively new technology called optical navigation, uses a camera to take pictures of the Earth, Moon and stars and autonomously triangulate Orion’s position from the photos. Its backup emergency communications system doesn’t use the primary system or antennae for high-rate data transfer.

Keep up with all the latest news on our newest, state-of-the art spacecraft by following NASA Orion on Facebook and Twitter.

More on our Moon to Mars plans, here.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

We’re Turning up the Heat on the Artemis I Spacecraft 🔥

The Orion spacecraft for Artemis I is headed to Ohio, where a team of engineers and technicians at our Plum Brook Station stand ready to test it under extreme simulated in-space conditions, like temperatures up to 300°F, at the world’s premier space environments test facility.

Why so much heat? What’s the point of the test? We’ve got answers to all your burning questions.

Here, in the midst of a quiet, rural landscape in Sandusky, Ohio, is our Space Environments Complex, home of the world’s most powerful space simulation facilities. The complex houses a massive thermal vacuum chamber (100-foot diameter and 122-foot tall), which allows us to “test like we fly” and accurately simulate space flight conditions while still on the ground.

Orion’s upcoming tests here are important because they will confirm the spacecraft’s systems perform as designed, while ensuring safe operation for the crew during future Artemis missions.

Tests will be completed in two phases, beginning with a thermal vacuum test, lasting approximately 60 days, inside the vacuum chamber to stress-test and check spacecraft systems while powered on.

During this phase, the spacecraft will be subjected to extreme temperatures, ranging from -250°F to 300 °F, to replicate flying in-and-out of sunlight and shadow in space.

To simulate the extreme temperatures of space, a specially-designed system, called the Heat Flux, will surround Orion like a cage and heat specific parts of the spacecraft during the test. This image shows the Heat Flux installed inside the vacuum chamber. The spacecraft will also be surrounded on all sides by a cryogenic-shroud, which provides the cold background temperatures of space.

We’ll also perform electromagnetic interference tests. Sounds complicated, but, think of it this way. Every electronic component gives off some type of electromagnetic field, which can affect the performance of other electronics nearby—this is why you’re asked to turn off your cellphone on an airplane. This testing will ensure the spacecraft’s electronics work properly when operated at the same time and won’t be affected by outside sources.

What’s next? After the testing, we’ll send Orion back to our Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where it will be installed atop the powerful Space Launch System rocket in preparation for their first integrated test flight, called Artemis I, which is targeted for 2020.

To learn more about the Artemis program, why we’re going to the Moon and our progress to send the first woman and the next man to the lunar surface by 2024, visit: nasa.gov/moon2mars.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

From Earth to the Moon: How Are We Getting There?

More than 45 years since humans last set foot on the lunar surface, we’re going back to the Moon and getting ready for Mars. The Artemis program will send the first woman and next man to walk on the surface of the Moon by 2024, establish sustainable lunar exploration and pave the way for future missions deeper into the solar system.

Getting There

Our powerful new rocket, the Space Launch System (SLS), will send astronauts aboard the Orion spacecraft a quarter million miles from Earth to lunar orbit. The spacecraft is designed to support astronauts traveling hundreds of thousands of miles from home, where getting back to Earth takes days rather hours.

Lunar Outpost

Astronauts will dock Orion at our new lunar outpost that will orbit the Moon called the Gateway. This small spaceship will serve as a temporary home and office for astronauts in orbit between missions to the surface of the Moon. It will provide us and our partners access to the entire surface of the Moon, including places we’ve never been before like the lunar South Pole. Even before our first trip to Mars, astronauts will use the Gateway to train for life far away from Earth, and we will use it to practice moving a spaceship in different orbits in deep space.

Expeditions to the Moon

The crew will board a human landing system docked to the Gateway to take expeditions down to the surface of the Moon. We have proposed using a three-stage landing system, with a transfer vehicle to take crew to low-lunar orbit, a descent element to land safely on the surface, and an ascent element to take them back to the Gateway.

Return to Earth

Astronauts will ultimately return to Earth aboard the Orion spacecraft. Orion will enter the Earth’s atmosphere traveling at 25,000 miles per hour, will slow to 300 mph, then parachutes will deploy to slow the spacecraft to approximately 20 mph before splashing down in the Pacific Ocean.

Red Planet

We will establish sustainable lunar exploration within the next decade, and from there, we will prepare for our next giant leap – sending astronauts to Mars!

Discover more about our plans to go to the Moon and on to Mars: https://www.nasa.gov/moontomars

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

We Like Big Rockets and We Cannot Lie: Saturn V vs. SLS

On this day 50 years ago, human beings embarked on a journey to set foot on another world for the very first time.

At 9:32 a.m. EDT, millions watched as Apollo astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins lifted off from Launch Pad 39A at the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, flying high on the most powerful rocket ever built: the mighty Saturn V.

As we prepare to return humans to the lunar surface with our Artemis program, we’re planning to make history again with a similarly unprecedented rocket, the Space Launch System (SLS). The SLS will be our first exploration-class vehicle since the Saturn V took American astronauts to the Moon a decade ago. With its superior lift capability, the SLS will expand our reach into the solar system, allowing astronauts aboard our Orion spacecraft to explore multiple, deep-space destinations including near-Earth asteroids, the Moon and ultimately Mars.

So, how does the Saturn V measure up half a century later? Let’s take a look.

Mission Profiles: From Apollo to Artemis

Saturn V

Every human who has ever stepped foot on the Moon made it there on a Saturn V rocket. The Saturn rockets were the driving force behind our Apollo program that was designed to land humans on the Moon and return them safely back to Earth.

Developed at our Marshall Space Flight Center in the 1960s, the Saturn V rocket (V for the Roman numeral “5”) launched for the first time uncrewed during the Apollo 4 mission on November 9, 1967. One year later, it lifted off for its first crewed mission during Apollo 8. On this mission, astronauts orbited the Moon but did not land. Then, on July 16, 1969, the Apollo 11 mission was the first Saturn V flight to land astronauts on the Moon. In total, this powerful rocket completed 13 successful missions, landing humans on the lunar surface six times before lifting off for the last time in 1973.

Space Launch System (SLS)

Just as the Saturn V was the rocket of the Apollo generation, the Space Launch System will be the driving force behind a new era of spaceflight: the Artemis generation.

During our Artemis missions, SLS will take humanity farther than ever before. It is the vehicle that will return our astronauts to the Moon by 2024, transporting the first woman and the next man to a destination never before explored – the lunar South Pole. Over time, the rocket will evolve into increasingly more powerful configurations to provide the foundation for human exploration beyond Earth’s orbit to deep space destinations, including Mars.

SLS will take flight for the first time during Artemis 1 where it will travel 280,000 miles from Earth – farther into deep space than any spacecraft built for humans has ever ventured.

Size: From Big to BIGGER

Saturn V

The Saturn V was big.

In fact, the Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center is one of the largest buildings in the world by volume and was built specifically for assembling the massive rocket. At a height of 363 feet, the Saturn V rocket was about the size of a 36-story building and 60 feet taller than the Statue of Liberty!

Space Launch System (SLS)

Measured at just 41 feet shy of the Saturn V, the initial SLS rocket will stand at a height of 322 feet. Because this rocket will evolve into heavier lift capacities to facilitate crew and cargo missions beyond Earth’s orbit, its size will evolve as well. When the SLS reaches its maximum lift capability, it will stand at a height of 384 feet, making it the tallest rocket in the world.

Power: Turning Up the Heat

Saturn V

For the 1960s, the Saturn V rocket was a beast – to say the least.

Fully fueled for liftoff, the Saturn V weighed 6.2 million pounds and generated 7.6 million pounds of thrust at launch. That is more power than 85 Hoover Dams! This thrust came from five F-1 engines that made up the rocket’s first stage. With this lift capability, the Saturn V had the ability to send 130 tons (about 10 school buses) into low-Earth orbit and about 50 tons (about 4 school buses) to the Moon.

Space Launch System (SLS)

Photo of SLS rocket booster test

Unlike the Saturn V, our SLS rocket will evolve over time into increasingly more powerful versions of itself to accommodate missions to the Moon and then beyond to Mars.

The first SLS vehicle, called Block 1, will weigh 5.75 million pounds and produce 8.8 million pounds of thrust at time of launch. That’s 15 percent more than the Saturn V produced during liftoff! It will also send more than 26 tons beyond the Moon. Powered by a pair of five-segment boosters and four RS-25 engines, the rocket will reach the period of greatest atmospheric force within 90 seconds!

Following Block 1, the SLS will evolve five more times to reach its final stage, Block 2 Cargo. At this stage, the rocket will provide 11.9 million pounds of thrust and will be the workhorse vehicle for sending cargo to the Moon, Mars and other deep space destinations. SLS Block 2 will be designed to lift more than 45 tons to deep space. With its unprecedented power and capabilities, SLS is the only rocket that can send our Orion spacecraft, astronauts and large cargo to the Moon on a single mission.

Build: How the Rockets Stack Up

Saturn V

The Saturn V was designed as a multi-stage system rocket, with three core stages. When one system ran out of fuel, it separated from the spacecraft and the next stage took over. The first stage, which was the most powerful, lifted the rocket off of Earth’s surface to an altitude of 68 kilometers (42 miles). This took only 2 minutes and 47 seconds! The first stage separated, allowing the second stage to fire and carry the rest of the stack almost into orbit. The third stage placed the Apollo spacecraft and service module into Earth orbit and pushed it toward the Moon. After the first two stages separated, they fell into the ocean for recovery. The third stage either stayed in space or crashed into the Moon.

Space Launch System (SLS)

Much like the Saturn V, our Space Launch System is also a multi-stage rocket. Its three stages (the solid rocket boosters, core stage and upper stage) will each take turns thrusting the spacecraft on its trajectory and separating after each individual stage has exhausted its fuel. In later, more powerful versions of the SLS, the third stage will carry both the Orion crew module and a deep space habitat module.

A New Era of Space Exploration

Just as the Saturn V and Apollo era signified a new age of exploration and technological advancements, the Space Launch System and Artemis missions will bring the United States into a new age of space travel and scientific discovery.

Join us in celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing and hear about our future plans to go forward to the Moon and on to Mars by tuning in to a special two-hour live NASA Television broadcast at 1 p.m. ET on Friday, July 19. Watch the program at www.nasa.gov/live.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Planes, Trains and Barges: How We’re Moving Our Artemis 1 Rocket to the Launchpad

Our Space Launch System rocket is on the move this summer — literally. With the help of big and small businesses in all 50 states, various pieces of hardware are making their way to Louisiana for manufacturing, to Alabama for testing, and to Florida for final assembly. All of that work brings us closer to the launch of Artemis 1, SLS and Orion’s first mission to the Moon.

By land and by sea and everywhere in between, here’s why our powerful SLS rocket is truly America’s rocket:

Rollin’ on the River

The SLS rocket will feature the largest core stage we have ever built before. It’s so large, in fact, that we had to modify and refurbish our barge Pegasus to accommodate the massive load. Pegasus was originally designed to transport the giant external tanks of the space shuttles on the 900-mile journey from our rocket factory, Michoud Assembly Facility, in New Orleans to Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Now, our barge ferries test articles from Michoud along the river to Huntsville, Alabama, for testing at Marshall Space Flight Center. Just a week ago, the last of four structural test articles — the liquid oxygen tank — was loaded onto Pegasus to be delivered at Marshall for testing. Once testing is completed and the flight hardware is cleared for launch, Pegasus will again go to work — this time transporting the flight hardware along the Gulf Coast from New Orleans to Cape Canaveral.

Chuggin’ along

The massive, five-segment solid rocket boosters each weigh 1.6 million pounds. That’s the size of four blue whales! The only way to move the components for the powerful boosters on SLS from Promontory, Utah, to the Booster Fabrication Facility and Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy is by railway. That’s why you’ll find railway tracks leading from these assembly buildings and facilities to and from the launch pad, too. Altogether, we have about 38-mile industrial short track on Kennedy alone. Using a small fleet of specialized cars and hoppers and existing railways across the US, we can move the large, bulky equipment from the Southwest to Florida’s Space Coast. With all the motor segments complete in January, the last booster motor segment (pictured above) was moved to storage in Utah. Soon, trains will deliver all 10 segments to Kennedy to be stacked with the booster forward and aft skirts and prepared for flight.

It’s a bird, it’s a plane, no, it’s super Guppy!

A regular passenger airplane doesn’t have the capacity to carry the specialized hardware for SLS and our Orion spacecraft. Equipped with a unique hinged nose that can open more than 200 degrees, our Super Guppy airplane is specially designed to carry the hulking hardware, like the Orion stage adapter, to the Cape. That hinged nose means cargo is actually loaded from the front, not the back, of the airplane. The Orion stage adapter, delivered to Kennedy in 2018, joins to the rocket’s interim cryogenic propulsion stage, which will give our spacecraft the push it needs to go to the Moon on Artemis 1. It fit perfectly inside the Guppy’s cargo compartment, which is 25 feet tall and 25 feet wide and 111 feet long.

All roads lead to Kennedy

In the end, all roads lead to Kennedy, and the star of the transportation show is really the “crawler.” Rolling along at a delicate 1 MPH when it’s loaded with the mobile launcher, our two crawler-transporters are vital in bringing the fully assembled rocket to the launchpad for each Artemis mission. Each the size of a baseball field and powered by locomotive and large power generator engines, one crawler-transporter is able to carry 18 million pounds on the nine-mile journey to the launchpad. As of June 27, 2019, the mobile launcher atop crawler-transporter 2 made a successful final test roll to the launchpad, clearing the transporter and mobile launcher ready to carry SLS and Orion to the launchpad for Artemis 1.

Dream Team

It takes a lot of team work to launch Artemis 1. We are partnering with Boeing, Northrop Grumman and Aerojet Rocketdyne to produce the complex structures of the rocket. Every one of our centers and more than 1,200 companies across the United States support the development of the rocket that will launch Artemis 1 to the Moon and, ultimately, to Mars. From supplying key tools to accelerate the development of the core stage to aiding the transportation of the rocket closer to the launchpad, companies like Futuramic in Michigan and Major Tool & Machine in Indiana, are playing a vital role in returning American astronauts to the Moon. This time, to stay. To stay up to date with the latest SLS progress, click here.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Known as the Horsehead Nebula – but you can call it Starbiscuit.

Found by our Hubble Space Telescope, this beauty is part of a much larger complex in the constellation Orion.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

How We’re Accelerating Our Missions to the Moon

Our Space Launch System isn’t your average rocket. It is the only rocket that can send our Orion spacecraft, astronauts and supplies to the Moon. To accomplish this mega-feat, it has to be the most powerful rocket ever built. SLS has already marked a series of milestones moving it closer to its first launch, Artemis.

Here are four highlights you need to know about — plus one more just on the horizon.

Counting Down

Earlier this month, Boeing technicians at our Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans successfully joined the top part to the core stage with the liquid hydrogen tank. The core stage will provide the most of the power to launch Artemis 1. Our 212-foot-tall core stage, the largest the we have ever built, has five major structural parts. With the addition of the liquid hydrogen tank to the forward join, four of the five parts have been bolted together. Technicians are finishing up the final part — the complex engine section — and plan to bolt it in place later this summer.

Ready to Rumble

This August, to be exact. That’s when the engines for Artemis 1 will be added to the core stage. Earlier this year, all the engines for the first four SLS flights were updated with controllers, tested and officially cleared “go” for launch. We’ve saved time and money by modifying 16 RS-25 engines from the space shuttle and creating a more powerful version of the solid rocket boosters that launched the shuttle. In April, the last engine from the shuttle program finished up a four-year test series that included 32 tests at our Stennis Space Center near Bay St. Louis, Mississippi. These acceptance tests proved the engines could operate at a higher thrust level necessary for deep space travel and that new, modernized flight controllers —the “brains” of the engine — are ready to send astronauts to the Moon in 2024.

Getting a Boost

Our industry partners have completed the manufacture and checkout of 10 motor segments that will power two of the largest propellant boosters ever built. Just like the engines, these boosters are designed to be fast and powerful. Each booster burns six tons of propellant every second, generating a max thrust of 3.6 million pounds for two minutes of pure awesome. The boosters will finish assembly at our Kennedy Space Center in Florida and readied for the rocket’s first launch in 2020. In the meantime, we are well underway in completing the boosters for SLS and Orion’s second flight in 2022.

Come Together

Meanwhile, other parts of the rocket are finished and ready for the ride to the Moon. The final piece of the upper part of the rocket, the launch vehicle stage adapter, will soon head toward Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Two other pieces, including the interim cryogenic propulsion stage that will provide the power in space to send Orion on to the Moon, have already been delivered to Kennedy.

Looking to the Future

Our engineers evaluated thousands of designs before selecting the current SLS rocket design. Now, they are performing critical testing and using lessons learned from current assembly to ensure the initial and future designs are up to the tasks of launching exploration missions for years to come. This real-time evaluation means engineers and technicians are already cutting down on assembly time for future mission hardware, so that we and our partners can stay on target to return humans to the Moon by 2024 — to stay so we can travel on to Mars.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.